This post is divided in 5 sections that provide a chronological account of the known history of the Goths, ranging from their transfer to the Western Roman Empire’s province of Gallia Narbonensis, through to their conquest of Hispania, until the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. It is best understood as following this other post about the origin of the Goths, the last in a series of posts about the history of the goths (check this, this, this and this post) and is divided in the following sections:

- The first section then describes the movements of the Goths in the 33 years of the reign of Theodoric between 418 and 451, his appeasement of the Romans, the civil war between Johannes and Galla Placida in the aftermath of Constantius III’s death, the rivalries between Aetius, Bonifacius and Felix, the conquest of Carthage by the Visigoths and the Hunnic invasions of Attila.

- The second section considers the reigns of Theodoric II and Euric, the Visigothic consolidation and conquests of Hispania between 451 and 484CE facilitated by the struggle for power between the Roman aristocracy, the western army, the Visigoths and the Eastern Empire that culminated in the collapse of Roman power in the West.

- The third section covers the period between 484 and 700 and reviews the reign of Alaric II, his interaction with Clovis, the end of Visigoth hegemony in Gaul, the influence of Ostrogothic elites, the conquest of Hispania and the rising instability of Visigothic Kingdom, which became plagued by coups and regicides.

- The next section considers the Ummayad Invasion of Hispania, the establishment of Al-Andalus and the collapse of Visigothic power between 672CE and 824CE.

- The last section briefly reviews Reconquista and the period of 824CE onwards

The most interesting observation I make is the dichotomy between the continued the stability of one side against the instability of its opponent. The stability of Gothic leadership during the period of 408 to 501 contrasts with the chaotic disorder that underlies the collapse of Roman authority in the West as well as with the sequence of regicides that takes place after the death of Theodoric the Great Amal. While Theodoric II and Euric held the Goths together between 453 and 484, Rome sees a quick succession of Emperors. Petronius Probus follows Valentinian III, only to be himself followed by Avitus, who ends up replaced by Majorian, himself followed by Libius Severus, before the last push of Anthemius (sponsored by Leo), who is succeeded by Olybrius , Glycerius and Julius Nepos. However, the stability with which the Gothic kings were able to rule their kin disappears with the arrival of the Ostrogothic Theodoric the Great Amal and his competing elites, the wars of Justinian, the Byzantine foothold in southern Hispania and the rise of Islam.

Theodoric I’s reign (418 – 451): Consolidation amid a Collapsing West

Wallia was succeeded by a bastard of Alaric, Theodoric I, who reigned for 33 years in the unstable period between 418CE and 451CE. After the relative calm of the beginning of his reign between 418 and 421CE, the death of Emperor Constantius III created once again the instability among western Roman ranks necessary to facilitate the consolidation of Gothic holdings in Aquitania I and Novempopulania.

Shortly before Honorius death, the emperor appears to have had a falling out with his sister that pushed her to flee towards Constantinople. Thus, when he died, his general and officials split between those who supported Valentinian III, the son of Emperor Constantius III and Galla Placidia and those who supported the Anician-sponsored Johannes (423-425CE). We can easily deduce that Castinus, the most powerful man in the west at the time of Honorius’ death, was in favour of Johannes . We also know that Bonifacius was in favour of Valentinian III. We also know for a fact that Flavius Aetius was in favour of Johannes. Moreover, the survival and subsequent rise of Flavius Felix means that he was probably in favour of Valentinian III, if not neutral. This leaves Asterius as uncertain. Heather seems to assume he sided against Castinus , which is not necessarily the same as siding with Valentinian III, so he remains uncertain.

The rise of Johannes led to the successful invasion by Ardaburius and his son Aspar from the Eastern Roman Empire, the death of Johannes, the exile of Castinus and the recruitment of Aetius‘ Huns in 425CE. The result was to consolidate the struggle for power around Aetius, Flavius Felix and Bonifacius. Interestingly, Theodoric I‘s rule (418CE-451CE) tracks the reign of Valentinian III(419CE-455CE) quite closely.

Based on this instability, Theodoric I is recorded as having made 3 efforts at expansion:

- Within Gaul he attempts to capture Narbo in 426CE and then in 436CE but is stopped

- He also moved to assist the Roman Genereal Vitus in 442CE against the Suebi in Gallaecia.

Interestingly, in none of these instances was he able to make any territorial gains. Theodoric I, while long-lived did not really distinguish himself much by his conquests. Clearly this was not for lack of trying. His attempts to take Narbo clearly coincide with the internal struggles between Aetius and Flavius Felix (425CE-430CE) and between Aetius and Bonifacius/Sebastianus (432CE). Theodoric I‘s inability to take advantage of the fall of North-Africa to the Vandals in 435CE and the ease with which Valentinian III/Aetius agreed to peace, highlights how the focus of western Roman operations was in Gaul rather than Africa. It also highlights that the effect of that loss was not immediate and that the Empire was quite happy to give up the region in exchange for (non-credible) tribute (cash payments).

Where Theodoric I‘s reputation was built was during the 451CE Battle of Chalons, also known as the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, where his sacrifice and that of the Goths assisted Aetius in repelling the apparently invincible Attila the Hun. In the course of the battle and following the death of his father, it appears (or at least chroniclers of the time recorded it so) that Thorismund, Theodoric I’s eldest son, led a cavalry charge that tipped the Battle of Châlons in favour of the Romano-Gothic alliance. In the aftermath of his father’s death during the battle, Thorismund ruled the Visigoths from 451 to 453, when he was killed by his brother Theodoric II.

Theodoric II/Euric, Consolidation and the Hispanic Expansion (451-484CE)

Following the death of Valentinian III in March 455, the abandonment of Marcian left the choice of a new emperor in the hands of the local factions. At this time there were three factions within the western empire:

- The Italian senatorial elites were the landowners and so controlled the majority of economic resources to feed the empire, particularly after the fall of Carthage in 439. They also held a virtual monopoly over the bureaucracy of the empire. After the death of Valentinian IIIand during the reign of Marcian (450-457), the ties between the east and the west started to also erode due to the end of dynastic connections between the two royal houses, which lined the eastern court’s interests with those of the Roman senators.

- The traditional Roman army as it had existed in the time of Stilicho and Constantius III, although diminished seems to have maintained a semblance of hierarchical stability and army loyalty to its generals (to the extent that this applies throughout the history of the Roman Empire).

- The Visigoths were able to leverage on their military might and territorial holdings in Aquitania to expand their domain. Due to their vicinity to the Gallo-Roman aristocracy, the Goths were often able to play on their dislike of Italian elites and coerce them into joining their cause. The case of Avitus is a clear example of this.

Roman elites probably led by their most illustrious and wealthy members, the Anicii, were the first ones to get their way. They managed to get their man, Petronius Maximus, over the choice of the is palace guards (Maximianus) and the Army (Majorian). However his rule was short-lived ( 75 days between 17 March – 31 May 455). Having failed to gain the support of the Eastern Empire, he made Avitus his magister militum and sent him over to Tolosa to get the support of the Visigoths. However, he married Valentinian III‘s widow and cancelled her wedding to Huneric the son of Genseric, who had conquered Carthage in 439. In revenge the Vandals moved on Rome to sack the city. When the news arrived to Rome, the emperor, without an army to protect him decided to flee. Abandoned by his guards he was eventually caught by a mob who supposedly killed him on the spot.

The Visigoths were the second faction able to get its way. Upon hearing the news of Petronius Maximus death, Theodoric II acclaimed his guest Avitus as his own choice of emperor whom he elevated on 9 July 455. In a very thinly veiled attempt to extend his dominions, he then moved to reconquer Hispania on behalf of the Roman Empire. The last Roman representatives in Hispania that I have been able to find out about are

Asterius, who successfully campaigns in Hispania with the Visigoths in 419 and 420 on behalf of Constantius III.

The stability brought about by these endeavours are undermined by the instability that follows the death of Constantius III and the civil wars of Johannes and Valentinian III. Although the Alans are destroyed and the Vandals move south towards Carthage, the Suevi stayed in Gallaecia. As with every other fact about this period, our knowledge of Roman presence in Hispania at this stage is a very patchy. Andevotus was a dux of Baetica who was defeated by Rechila in 438. Censorius was a Roman comes sent to act as an ambassador to the Suevi in 442 and was killed by Agiulf in 448; Asteryus (a magister utriusque militae who fought against the Bagaudae in 441). Thus, from 441 onwards, all we can say for a fact is that the Rechila and the Bagaudae hold sway over Hispania.

Thus, when Theodoric II moves onto Hispania, his main opposition is from among the Suevi, which he is able to defeat after taking Narbo.

Avitus was a member of the Gallo-Roman aristocracy and had on occasion visited Theodoric during the reign of Valentinian III to serve as as a hostage or an intermediary between the Romans and the Visigoths. He had been an embassador of the defeated Gallo-Roman aristocracy to Constantius III after the downfall of Constantine III and Jovinus. He had been a hostage of and intermediary between the Visigoths and the Romans in 425/6. He joined the army and participated in Aetius‘ campaigns against the Jutungi (430/1) and the Norics and against the Burgundians (436) in Gaul and may have been appointed as magister militum per Galliae in 437 before being made Praetorian Prefect for Gaul in 439. He retired in 440 and only came back to intercede with the Visogoths to fight with the Romans against the Huns at Chalons in 451 after which he disappears once again until Petronius Maximus recalls him. He appears to have been altogether powerless so that having become familiar with him, the Goths felt comfortable using him.

However, although not as short as that of Petronius Maximus, Avitus’ rule was short-lived (1 year and 3 months between July 455 and October 456). That which made Avitus a good choice for the Visigoths and the Gallo-Romans made him undesirable to the Roman army and the Italian senators. Majorian and Ricimer had been side-lined by the appointment of Remistus as magister militum and the appointment of Gallo-Romans to staff the imperial administration of Avitus certainly displease the Italian senators, according to MacGeorge (2003:191-2). Once the Gothic regiment that he had been provided with by Theodoric II left, it was only a matter of time before Ricimer and Majorian moved against Avitus with the support of the Italian senators. Clear about the power dynamics at play, the Roman establishment still had enough vitality to make a push against the Visigoths.

The remaining military elite of the West was made up of Aetius‘ generals, including Majorian, Ricimer, Marcellinus (in Dalmatia), Nepotiamus and Aegidius (in Gaul). As MacGeorge (2003:196) argues, “the period immediately after [the defeat of Avitus at] Placentia, during which Majorian and Ricimer consolidated their positions, is very obscure (…)”. However, Sidonius describes the two as being united in “bonds of affection”. When Majorian (457-461) was chosen as Emperor first by the army’s acclamation in April 457 and then confirmed ratified by the Roman Senate in December 457, he seems to have had a strategic plan for restabilising the empire that included putting up a fight against Vandal raids in Italy, asserting imperial authority over (southern) Gaul, reconquering Hispania and take Carthage back the Vandals. While he was successful in the first three of these endeavours, the same is not true of the last and most important one of all. He recruited large amounts of barbarian mercenaries into the Roman army and built two navies to face off against the Vandals and appears to leave Ricimer in charge of Italy. With the help of Aegidius and Nepotiamus, Majorian campaigned in Gaul against the Visigoths and the Gallo-Romans of Lugdunum (Lyon) who had allied themselves with the Burgundians under Gundioc. The Goths of Theodoric II were defeated at the Battle of Arelate while the Gallo-Romans were pacified by a tax reduction rather than punished through arms. I

MacGeorge (2003:204-9) offers a good discussion of the campaign of Majorian into Spain in May 460 and how he ultimately failed to cross over to Africa because of the foresight of Geiseric who was able to uncover and take his fleet before Majorian’s forces could board it. MacGeorge (2003:209-14) then discusses how and why following this failure, Majorian returned to Italy in 461, only to be intercepted by Ricimer’s forces, who deposed and killed him. Failure and waste of resources on the scale that Majorian had just suffered was not acceptable.

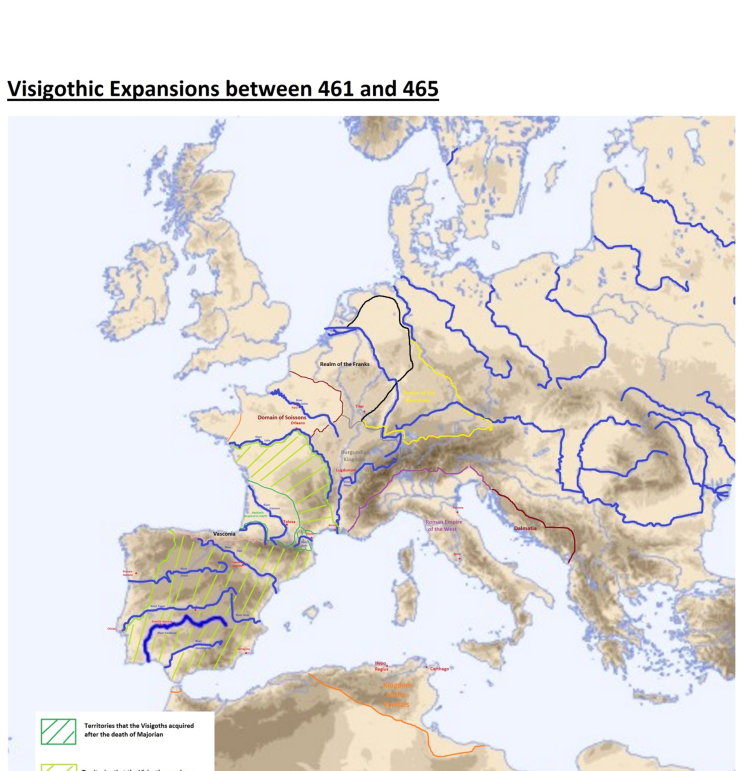

Following the death of Majorian, the Roman Empire folds onto its Italian self and what central authority had been re-established elsewhere suffers the ravages of abandonment. As always, because power hates vacuum, the absence of Roman authority created opportunities for expansion from other forces. Ricimer’s appointment of Lybius Severus appears to have not been met by the support of any of the other Roman military leaders (Aegidius, Nepotiamus and Marcellinus ). Thus he had to seek support from the Visigoths, which was achieved in exchange for granting Theodoric II the much-coveted Gallia Narbonensis in 462. This appears to have triggered a revolt of Aegidius in Gaul who may have allied himself with the Franks under Clovis’ father Childeric and the Bretons under Riothamus to contain the advance of the Goths at Orleans while also dealing with Saxon raids and Arbogast in Trier. Meanwhile, Marcellinus who had been left by Majorian in Sicily to deal with Vandal raids had some success but retired to Dalmatia to better liaise with Leo I in Constantinople. Finally, we know that Nepotiamus together with Sunieric the Goth defeated the Suevi at Scallabis and Lucus Augusta. Nepotiamus appears to have been captured by forces loyal to Theodoric II in the early 460s in Hispania. While it is not possible to say with any certainty who held what, the capture of the only high-ranking Roman General in Hispania in the after-math of Majorian’s death and the defeat of Visigoths at Orleans suggests a substantial if tentative expansion of Visigothic dominions during the last years of the reign of Theodoric II, coinciding with the reign of Lybius Severus.

With the murder of Theodoric II by Euric (466-484) and the rise of the latter to the throne of the Visigoths, the Goths begin to expand, filling the gap left by the twilight of Rome. Although Rome had one last breath of strength during the reign of Anthemius (467-472CE), this is more of a short-lived sigh.

The failure to capture Carthage at the battle of Cape Bon in 468 effectively bankrupts the west (and almost the east), destroys any hopes of reuniting the territories lost since 408 under a single Roman authority and postpones any hopes of reconquest of Vandal Africa for another 60 years until Belisarius. Anthemius’ further attempts at curtailing the advance of Euric resulted in defeat sometime after 470 when the emperor also sentenced to death a Roman senator, Romanus, allied with Ricimer, with whom he had never had good relations, which precipitated his own death in 472. Ricimer replaced Anthemius with by Olybrius, but the two died shortly thereafter, in August and December of the same year, respectively. Ricimer is replaced as military hegemon by his nephew, Gundobad who elevates Glycerius (473-474) to the purple, before moving on to better pastures as the king of the Burgundians from 473 to 516. Glycerius himself is ousted by Julius Nepos who is the last legitimate claimant to the West Roman throne, contrary to common belief. Orestes, eventually forced Nepos to flee and appointed his own son as the last Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus (475-476). Inevitably, Orestes inability to get lands for his soldiers from the Roman senators gets him killed and Romulus Augustulus deposed by Odoacer (433-493) who rules Italy de facto but official on behalf of Julius Nepos, until the Ostrogoths of Theodoric the Great Amal take over Italy on behalf of the eastern empire between 493 and 554.

Amid this chaos, Euric (466-484) and his Visigoths have not been wasting time. On the contrary, Euric consolidates the gains that Theodoric II made, defeats Riothamus in 470 (this Riothamus may have been a Roman contemporary called Ambrosius Aurelianus and the inspiration for King Arthur) and is recognised by the eastern emperor Zeno as independent king in 475. His codification of Visigothic law in 471 (Codex Euricianus) is a significant sign of legalistic continuity between Late Antiquity and the Dark ages.

Alaric II, Clovis, Ostrogothic influences in the Visigothic Kingdom and decline: 507-700

Euric is succeeded by Alaric II (484-507) who rules over the largest expanse of Visigothic territory. However, he has the misfortune of being a contemporary of the Salian Frank king Clovis, whose family had also been fighting with and against the Roman Empire for generations. After the conquest of the Ripuarian Franks at some undisclosed date, Clovis defeats the Romans of Syagrius at the Battle of Soissons, the Alemmani (at the Battle of Tolbiac in 496), and Gundobad‘s Burgunds (although not definitively) at Dijon in 500. Expanding southwards, Clovis eventually defeats the Visigoths at the 507 battle of Vouille, where Alaric II is killed. Prior to this, in 506, Alaric II had provided for the first revisions to Euric’s legal codes, contained in the Breviary of Alaric (506).

The areas in shades of orange in the map below show the Visigothic kingdom at its largest expanse during the reign of Alaric II. The area in dark orange corresponds to the original Aquitanian territory received from Constantius III, the intermediate orange area south of the Pyrenees is the reduced Hispanic kingdom after the 507 battle of Vouille.

With the death of Alaric II, his infant son Amalaric (511-531) succeeded him, under the guardianship of his maternal grand-father Theodoric the Great Amal, king of the Ostrogoths. This period is marked by the reacquisition of Aquitania and a range of territories lost to Clovis in 507, thanks to the support of Theodoric’s Ostrogoths.

Although the death of Theodoric the Great Amal in 526CE marks the end of Ostrogothic-Visigothic coordination, there seems to be a seemless integration of the Ostrogothic leaders sent by Theodoric to the Visigoths that speaks to the profound similarities between the two peoples, despite more than 100 years of separation.

The death of Alaric II also appears to signal the beginning of a period of internal struggle for power among the Visigoths.

- Five years after the death of Theodoric one of those generals, Theudis, murders the unpopular Amalaric and rules until 548. It is worth noting that Theudis is a contemporary of the Byzantine conquest of the Vandal Kingdom (523-530) and the first phase of the (Ostro)gothic wars (535–554) by Byzantium, a period of crisis for the Ostrogoths.

- Theudis is also killed and succeeded by Theudigel, one of his generals, who rules for 1 year between 548 and 549.

- Theudigel himself is murdered at a banquet and is succeeded by Agila.

- Agila (549-554) then faces rebellions from the city of Cordoba, whose Catholics opposed what may have been his relatively outspoken Arianism, and from Cantabrian landowners who elect their own self-governing senate.

- Upon Agila’s defeat by the Cordoban rebels, Athanagild opens a new front against the king in 551, defeating him in Seville. It is likely that, as Isidore of Seville argues, Athanagild called on the Byzantines for assistance (rather than it being Agila calling for Byzantine assistance as Jordannes says) given that upon their arrival in 552 the balance appears to have tipped in favour of Athanagild. However, this is not completely clear as the Byzantine intervention of 552 seems to have been mainly focused on the conquest of Provincia Spaniae.

- The rules of Theudigel (548-549), Agila (549-554) and Athanagild (554-557) coincide with the last phase of the (Ostro)gothic wars (535–554).

- Athanagild’s (554-567) rule was mainly concerned with the containment of Byzantine incursions from their foothold in the south. To this extent he was successful, even if he was unable to recapture Provincia Spaniae. The image below show the Visigothic kingdom in 560, during the rule of Athanagild (554-567), after Justinian’s conquest of the Vandal Kingdom (523-530), Justinian‘s 552 conquest of Provincia Spaniae and of the (Ostro)gothic wars (535–554).

- 5 months after the natural death of Athanagild’s in567, he is succeeded by a Visigothic noble called Liuva who is elected at Narbonne in Septimania, probably on account of Frankish threats. His reign is short and he dies of natural causes to be replaced by his brother, Liuvigild (568-586), who reforms the laws of the Visigothic Kingdom (Codex Revisus) to henceforth treat the Romans and the Visigoths as equal in The remaining 150 years witness the consolidation of Visigothic rule in Hispania. The rule of Liuvigild is characterised by the quasi-total conquest of the Iberian peninsula, save for the remaining Byzantine holdings in Spania. The map below shows the result of these conquests in 586

There are three fundamental developments taking place in the Iberian peninsula after the death of Liuvigild:

- His son Reccared (586–601), finally converts from Arianism to the Chalcedonian Catholic Christianity of his Hispano-Roman subjects in in 587, through the intervention of the brothers (Saints) Isidore of Seville and Leander of Seville.

- Between 610 and 619, the Visigoths go on the offensive against Byzantine Spania, during the reigns of Witteric (603-610), Gundemar (610-612) and Sisebut (612-621), until in 624 Suintila (621-631) brought the whole of the Iberian Peninsula Visigothic rule.

- Finally, from 631 until the 672, the kingdom is successively plagued by civil wars. Suintila is overthrown by Sisenand in 631.Sisenand (631-636) himself faced the rebellion of a certain Iudila. Tulga (640-642), son of Chintila (636-639) (successor of Sisenand) faced the rebellion of Chindasuint (642-653) who overthrew him and implemented a range of reforms to the civil administration of the kingdom. He was succeeded by his son Recceswinth (649-672), who had to deal with Basque rebellions.

The Ummayad Invasion and Al-Andalus: 672-824

By 700 the Goths held the whole iberian peninsula as well as the old Roman province of Septimania, in Gallia Nargonensis.

However, since 672, there had been arab raids on the coast of Baetica. The problem remained and worsened during the reigns Wamba (672-680), Erwig (680-687), Egica (687-702), his son and co-ruler Wittiza (694-710) and Roderic (710-712), who killed his predecessor.

The situation takes a turn to the worst from 711 onwards when a (mainly) Berber force of 12,000 soldiers sponsored by the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus and led by Tariq Ibn Ziyad landed in Spain.

There appear to be 3 decisive points in the conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom:

- The Battle of Guadalete in 711/712 marks the end of the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania at the hands of the Berber army of Ṭariq ibn Ziyad. The lead up to this battle and the manner in which the Berber army came to cross the straight of Gibraltar suggests that Roderic‘s behaviour and hubris may have caused his downfall.

- The Battle of Covadonga in 718 or 722, was a small battle, considered relatively unimportant by Umayyad leaders but the survival of Visigothic lords led by Pelagius created the necessary leadership for the beginning of the reconquista to take place from Asturias.

- The year of 732 marks the end of the independent Duchy of Aquitaineat the Battle of the River Garonne where Odo of Aquitaine is defeated by the Berbers. It also marks the end of the Umayyad expansion at the Battle of Poitier where Charles Martel led an alliance of Frankish lords to stop the Berber advance led by Abd Ar-Rahman Al Ghafiqi.

The Reconquista and the end of the Visigoths : 824 onwards

The Muslim conquest took close to 77 years to conclude, but by 788 the Umayyad Caliphate had completely obliterated the Visigothic kingdom, except for some few remnants. However, with some help from the Franks, these remnants created the roots for the rebellion that became the centuries long effort known as the Reconquista. To the North, the fiefs in Asturias that survived thanks to the efforts of Pelagius eventually expanded into the counties of

To the East, the Marches of Gothia and Hispania set the roots for

- the Frankish County in Barcelona after 801, and

- the Kingdom of Pamplona/Navarre from 824 and Aragon from 1035.

Of course, by the time the Reconquista was over, the world was very different and the Goths as an ethnic group native to the Iberian Peninsula no longer existed as such. The last discernible evidence of a Gothic culture is from an obscure community along the Crimean peninusla attested in the 18th century and of which very little is known. Paradoxically these would have been the Goths that never migrated into the Roman Empire. Winners are sometimes short-lived but they leave a memory, while the descendants of the defeated often disappear into the crowd of their invaders.

Conclusion

The history of the Goths is extremely insightful in my opinion. It speaks to the chaos of historical events, the internal (politics) and external (geopolitics) centrifugal forces driving migration, conquest, consolidation, integration and decline. While there are plenty of interesting legal, military, economic and political issues, there is nothing much heroic once the historical record is stripped of its religious and nationalistic propaganda.

The Goths did not defeat the Roman Empire. There was no decisive battle. The Romans and the Vandals defeated the Roman empire. This was not achived due to any particular weakness of the Roman Empire or particular superiority of the Vandals. It was a continuous 5 generation-long (Stilicho, Constantius, Aetius, Majorian and Anthemius) where the leaders of each stage came to slowly accept an increasingly reduced scope of action, which culminated with the loss of Carthage and the failure at Cape Bon. The Goths, much as the Franks and the Vandals were able to take advantage of Rome’s internal instabilities between each of these rulers by expanding their holdings. However, much remained the same. The elites remained Gallo- and Hispano-Roman as can be seen in St Isidore and in St Remigius conversions of their respective suzerains.

Similarly the Goths fall was not the fault of a particularly exceptional ability among the Berbers that conquered them as much as due to the division of the Goths. A similar issue with division can be found plaguing al-Andalus at the end of the Reconquista, as was the case at the end of the Roman Empire.

The conclusion in my opinion is that it is neither markets, nor race (although perhaps racism), nor necessarily enemies that destroy a state or statelet, but often it is the internal divisions of that very state that undermine its survival.